Barbour: not just a posh product.

How do you sell to the Queen, Alexa Chung and James Bond? Leave it to Dame Margaret Barbour.

There's a lovely quote in one of our early

catalogues," says Dame Margaret Barbour reading from the 1908 Barbour

brochure in her sing-songy, slightly Alan Bennett-ish lilt: " 'Wherever

men need to be protected, Barbours will do it for you.' You see?" she says

triumphantly, "we were never just an upper-class product."

I have been in Dame Margaret's beige and brown office

barely 10 minutes and the C word has already been uttered. Inevitable really.

Three royal warrants - from HM the Queen, HRH the Duke of Edinburgh and HRH the

Prince of Wales - adorn one of the walls. Outside her window, a view of the

fields of Tyne and Wear unfolds. This is a rural brand for hunters, shooters

and fishers.

Except not quite. We may be surrounded by bucolic

ruggedness, but we're also on a small industrial estate. And Barbour is as

popular with the Hoxton Farmers (groovy east Londoners who began buying up

original baggy Barbours in the Noughties to wear with their box-fresh trainers)

as it is with the Duke of Edinburgh. More so, possibly, because the Duke once

referred to the wondrous waxed, all-weather Barbours as "those smelly,

sweaty, sticky old jackets". Hoxton Farmers - and the many fashion editors

who also adore the brand - would never permit themselves such lèse majesté.

Also, they know that thanks to improved wax, Barbours are now neither sticky

nor smelly.

Hackney Farmers fuel resurgence in Barbour jackets.

That Barbour has successfully steered a tightrope

between fashion and function, is almost entirely down to Dame Margaret who,

truth be told, is not much of a sportswoman, although she does like walking her

spaniel, Goldie. But wisely, she has always imported the expertise of sportier

souls, such as the racing driver Jackie Stewart, the jockey Willie Carson, the

eventer Captain Mark Phillips and Lord James Percy (who, according to Barbour's

website, is "one of the outstanding shots of his generation") to

maintain credible sporting credentials.

Simultaneously, there have been fashion collaborations

with Anya Hindmarch, Sir Paul Smith and Alice Temperley. The next, out in July,

is a capsule collection of tweed hunting jackets designed by Chanel muse and

keen equestrian Amanda Harlech, which brings the spirit of Dior's New Look to

the shires (and, no doubt, Shoreditch).

Barbour had being going long before Dame Margaret was a twinkle in the eyes of her insurance salesman father and her greengrocer mother. In 1894, John Barbour, originally of Galloway, founded the company in South Shields, making coats out of oilcloth imported from Scotland. The Admiralty became an enthusiastic customer during the First World War, as did trawlermen, shepherds, the police and submariners - nobody posh. In 1934, Duncan Barbour, John's grandson and a keen motorcyclist, introduced the biking jackets that became the uniform of every British international motorcycling team - and, later on, of Steve McQueen. Not posh either, but stylish.

By the time Margaret Davies, as she then was, met John Barbour in 1964, the company, which was being run by Duncan's widow, Nancy - or Granny Barbour, as Dame Margaret calls her - was turning over £100,000 a year.

Wax without wane: Barbour's fashion resurrection.

It was solid, comfortable and respectable. Margaret settled down to life as an art teacher, married to a man who had trained as an architect and whose wild side was expressed in a shared family passion for motorbikes. Then in 1968, when she was just 29 with a two-year-old daughter, John Barbour suddenly died from a brain haemorrhage.

Granny Barbour and Margaret were at the helm. Daughter and mother-in-law sounds like a recipe for fractiousness, but Dame Margaret says it was fine "because Granny was boss and I was doing sales, marketing and a bit of designing".

Although Granny Barbour was no fool, she had a Situation on her hands with a member of staff who was directing the business to hell in a handcart. It took a high court case to get rid of that problem. But like another Margaret, who was the offspring of a greengrocer, Dame Margaret is made of steely stuff. She observed what the Italians and French were up to "and pinched a few ideas from them". She plugged gaps in the range, introduced navy where there had only been olive and brown, staved off advances from bigger companies who wanted to buy Barbour & Sons on the cheap, launched new styles and took care not to slap Barbour's name on anything she considered "nasty and undeserving of the Barbour association".

She also commissioned an exclusive tartan for Barbour's linings ("Can you imagine, until then they didn't have their own?") and raised her daughter Helen. What with Granny Barbour and Dame Margaret's mother, who moved in to look after Helen, Barbour was an early incubator of Girl Power.

And then the Eighties happened, Sloane Rangers began appearing in Barbours on the King's Road and sales went mad. Dame Margaret never allowed the product's fashionability to get out of hand. "Oh no. I always said we had to keep moving the design on, so that if women wanted a shorter, narrower fit, it was there. But we also had to respect the core products. It had to be authentic."

Most of all, the jackets are still made in the UK, apart from some leather goods and flyweight jackets that are produced in Eastern Europe. "I pay a fortune for Caroline Charles for the same reason," she says: "it's thoroughly British."

She never wanted to "do a Burberry". "That would not be our style," she says firmly, although she always foresaw that Barbour could be more than £100,000-a-year brand.

Shire attire gets streetwise.

However, sometimes destiny is taken out of one's hands. If fashionistas decide whiffy, vintage Barbours are It one year and Over the next, there's not much Dame Margaret can do. In the early Nineties, post-Sloane Ranger mania and thanks to a few mild winters, sales dipped. Cannily, Dame Margaret expanded the design team to ensure the product range adapted to modern tastes, introduced lighter weights and relaunched the motorcycling range, which had been phased out in the Seventies in the face of competition from the likes of Belstaff. That was a key decision.

The motorcycle range is now 25 per cent of Barbour's growth (turnover this year is running at £135 million). It's not just that biker jackets and quilting are bona fide classics, but that Barbour's motorbiking heritage is genuine.

These days, any brand that wants to survive must harness the growth hormone that is fashion, and Dame Margaret, her daughter Helen, who now works in the business, and managing director Steve Buck have a highly nuanced understanding of it. "Men's fashion needs to be quirky," says Buck. "Then again, if I suggest something that's wrong, Dame Margaret [all her staff call her Dame Margaret] will say, we did that in the Seventies and it didn't work."

One quirky men's initiative that has worked is the Tokihito Yoshida-designed To Ki To Beacon Heritage jacket that Daniel Craig wears in Skyfall. Demand has vastly outstripped supply. For the first time, sales in the UK now exceed exports. Is it all those flashy non-doms moving to Surrey and taking up rural life? "I don't think we're quite on their radar yet," says Dame Margaret. Her tone says it all.

Now 72 and married to her second husband, an architect, for 26 years, Dame Margaret comes into the office three days a week and spends the rest of her time on Barbour's charitable foundation - and walking Goldie. I daresay even those South Shields gales don't ruffle her immaculate blonde hair (she has it blow‑dried twice a week) or penetrate those Barbours. She may consider herself merely "the custodian of the brand, for the next, sixth generation", but that oilcloth is in her genes.

Armstrong, L., 27th March 2013, The Telegraph

Why city kids like me are on the hunt for Barbour.

Shunning Burberry's elitism, Barbour

has embraced its urban fans and headed for the high street. Easy on the lambing

jokes.

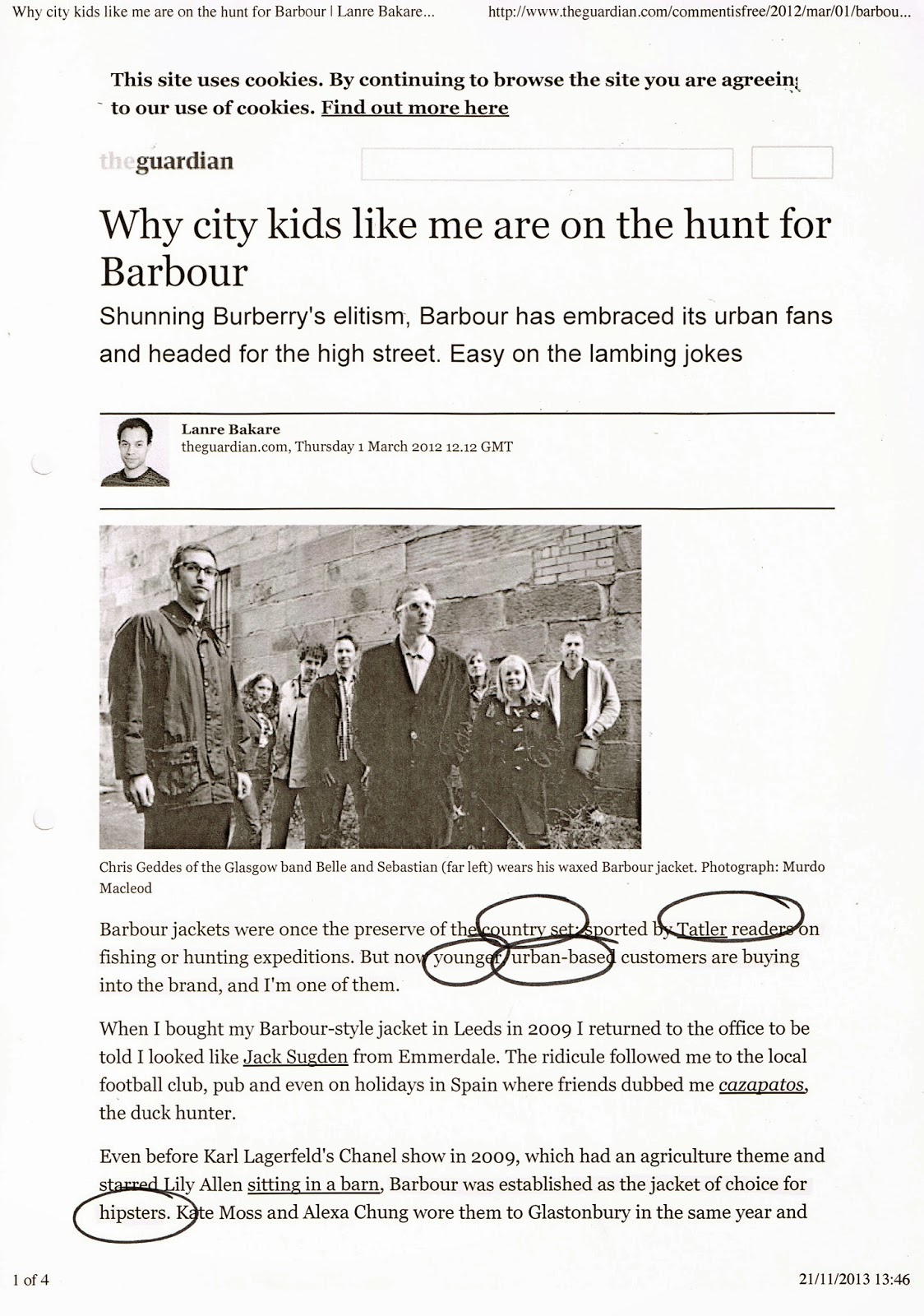

Barbour jackets were once the preserve of the country set; sported by Tatler readers on fishing or hunting expeditions. But now younger, urban-based customers are buying into the brand, and I'm one of them.

When I bought my Barbour-style jacket in Leeds in 2009 I returned to the office to be told I looked like Jack Sugden from Emmerdale. The ridicule followed me to the local football club, pub and even on holidays in Spain where friends dubbed me cazapatos, the duck hunter.

Even before Karl Lagerfeld's Chanel show in 2009, which had an agriculture theme and starred Lily Allen sitting in a barn, Barbour was established as the jacket of choice for hipsters. Kate Moss and Alexa Chung wore them to Glastonbury in the same year and now Barbour-style jackets are all over the high street and on Asos.

It's easy to scoff at the "Hackney farmers" for buying into yet another ridiculous hipster trend. But the brand has become popular beyond the world of Dalston Superstars. Real people like the brand too. Now there's more chance of someone asking me where I got my jacket than asking me how the lambing season is going.

Quilted, waxed, traditional green, sleek black, bright pink, however they come, Barbour jackets have proved so popular that the company recorded an increased turnover of £123m last year, up around £30m from 2010. Traditional fans have begun to mutter about what happened to Burberry in the mid-noughties when it became synonymous with "chav culture" rather than luxury chic and its traditional fashion base disappeared and sales plummeted. It took an expensive rebranding exercise featuring Mario Testino and Emma Watson to revive its elitist edge.

But Barbour is more open to its new customer base, providing alternative (more youthful) colours to its range. There's even talk of a more extensive fashion range being developed at its South Shields base in the north east.

So for all the ridicule, the trend has at least led to a revival which is bolstering a UK-based company with a workforce in one of the most economically challenging areas of the country.

There's a school of thought that says in times of austerity people look up to how the other half live, by watching programmes like Downton Abbey or buying brands like Burberry, Barbour or "luxury items" and at least looking like you can afford to splash out. Barbour's success is in part down to that aspirational drive, but it's also down to working-class shoppers putting aside its image of toff chic and making it their own.

Barbour is succeeding where Burberry went wrong by inviting everyone to wear one of its jackets rather than vainly trying to limit them to just an elite few.

Bakare, L., 1st March 2012, The Guardian

I initially highlighted all relevant areas of the articles. With these highlighted areas I then picked out the most important and relevant words, allowing me to gain a greater understanding of my audience.

From

these two articles and other research I have done (survey), Barbour’s market has not

changed but developed and expanded over the years it has been in business.

Traditional

Wearers

-

Country Set

-

Tatler Readers

-

Fishermen

-

Hunters

-

Shooters

-

Admiralty

-

Trawler men

-

Shepherds

-

Police

-

Submariners

-

(Royals)

-

Motorcyclists

-

Equestrians

-

Elite

Contemporary

Wearers

-

Country Set

-

Tatler Readers

-

Fishermen

-

Hunters

-

Shooters

-

Admiralty

-

Trawler men

-

Shepherds

-

Police

-

Submariners

-

Royals

-

Motorcyclists

-

Equestrians

-

Elite

-

Hipsters

-

‘Hackney Farmers’

-

‘Dalston Superstars’

-

Fashion editors

-

‘Sloane Rangers’

The

overwhelming opinion I have gathered from my research is that Barbour is a

brand for ‘everyone’ and unlike Burberry has embraced this. Barbour’s claim

that it is all-inclusive is, however, flawed. Due to the price of the products

it is only available to everyone who can afford it. They are expensive item,

yet they are designed to last a lifetime and therefore that must be considered

when dissecting the audience.

Even

though there is such a wide audience, there are themes throughout.

Due

to its heritage the company is very traditional whilst also embracing the

modern and contemporary. This is something that is reflected in the diversity

of the audience.

The

website should therefore reflect that and combine the traditional with the

modern, as Norton & Sons did with there recent rebrand.

On

top of the brands heritage there is also the price level that must be

considered. The website cannot look cheap and should appear sophisticated and

professional.

This

is a family run business with a very strong history and a unique product.

The

website must reflect the brands traditional values whilst giving it a

contemporary feel to engage both the traditional wearers and the new wearers.

No comments:

Post a Comment